Mary Affee Mary Affee In our final episode of Season 1 on Finding the Helpers, we have an interview that manages to tie all our other interviews beautifully together. Mary Affee is a licensed clinical social worker, PhD candidate, and specializes in play and trauma therapy. She left her bustling practice in North Carolina to return to her original home of New York City for four weeks to be a therapeutic presence for frontline medical staff in hospitals as they faced the height of New York’s COVID-19 peak. Like many front line staff and our other interviewees, Mary stressed a few times during this interview that she is not a hero. Mary’s daughter was diagnosed with cancer at 16 years old, and Mary truly saw this deployment to New York as her time to pay it back to the medical staff who saved her daughter’s life. As we listened to Mary’s story, it was clear to us that with her clinical background, personal experiences, and the four weeks she spent working in New York hospitals, that Mary was not only going to help us share another powerful story, but that she tied together so many of the profound lessons we have learned through these interviews in the past four months. Mary was set up in the hospital in New York with art supplies and creative activities in the same place every day, showing up as consistent, predictable support, equipped with the ability to administer psychological first aid and/or crisis interventions for hospital staff. She shares a personal story of her work, when she interacted with a cleaning professional in the hospital, “[When] people think first responders, they think of medical staff. Often we overlook people in housekeeping. I mean, they are right there cleaning up.” The cleaning staff noticed that Mary was going to be leaving soon, and came to her and asked for a painted rock. Mary, being an expressive therapist, initially noticed her instinct to want to encourage this woman to create her own rock, but the woman was insistent on having one that was already painted. The woman then said to Mary, “I want something to always remember you by.” Mary goes on to say, “It took my breath away. You never know what a smile will do for somebody.” When Mary says you never know how a connection is going to affect someone, she is talking about exactly what Laura Fuchs, the photographer in NYC, taught us when she described her work with the mask smiles project -- that you can, in fact, smile at someone through a mask. Additionally, they taught us how small acts, such as showing up in the same place every day to show support, or simply smiling at a stranger, can plant a seed in someone which has the potential to grow beyond what we could ever imagine. Laura also reminded us that, we never really know the complete ripple effect of how reaching out for connection will land on someone. This makes taking the risk and reaching out, especially right now, absolutely worth it. “Just love people, be present, be real, be authentic. Those are the things that keep it real, keep us human, keep us in a shared experience.”

0 Comments

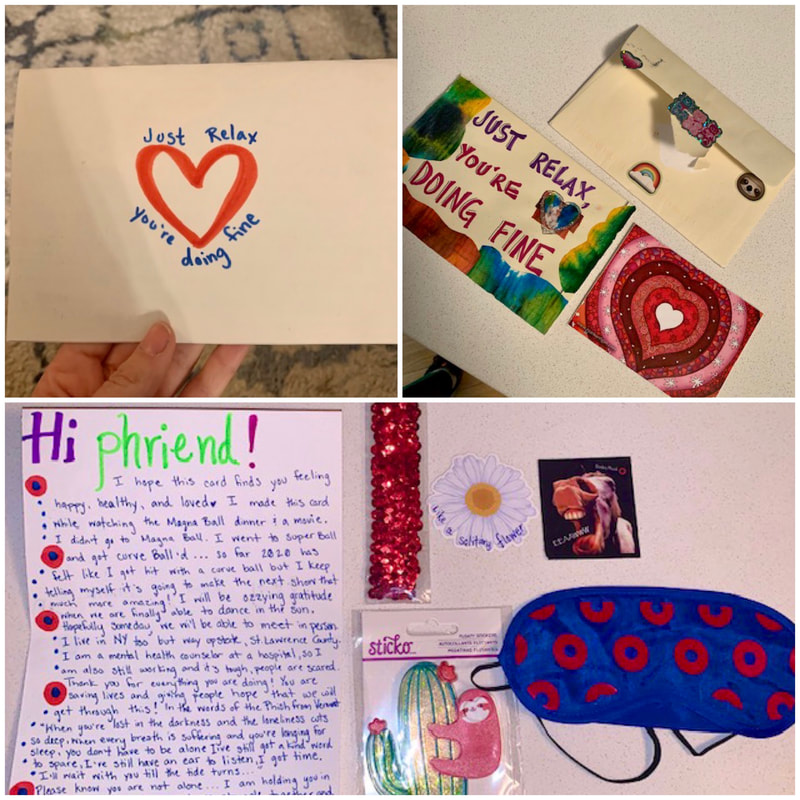

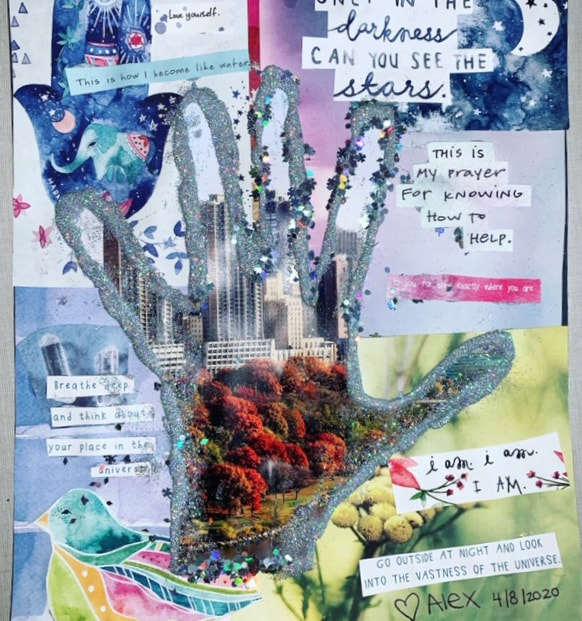

Isaac Cosmas Isaac Cosmas In this episode of Finding the Helpers, we had the pleasure of speaking with Isaac Cosmas, a South Sudanese refugee who Playing to Live met while conducting a mental health needs assessment in Rhino camp, a refugee settlement in Uganda. Isaac was there as both a refugee and working as part of the frontline staff providing supporting the mental health needs of other refugees. In his interview, Isaac shares with us his story of struggle, resilience, and brings to light the hardships facing refugees during a global pandemic. Isaac was born during the second Sudanese civil war which had broken out in the early 1980s. This conflict lasted for almost two decades and was based in the same cultural, religious, and language differences of previous conflicts between Sudan and South Sudan. Due to this conflict, Isaac spent the first portion of his life within the same village he was born in. Isaac described always being driven toward education. That learning was a top priority for him, but that in his village school did not go beyond primary school and most of his teachers had not completed anything beyond primary school themselves. He says, “We never had any hope for progressing in education, or getting exposed to the world, or associating with people of different cultures because we never had the chance of interaction. The village that I was living in was the whole world that I knew.” It wasn't until The Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed in 2005 that he got the chance to venture beyond the borders of his village. The South Sudanese could finally travel, obtain education, and meet new people outside of their villages. Isaac seized that opportunity to move to Uganda where he began pursuing higher education, eventually receiving a diploma in Religious studies. Once he obtained this degree, Isaac was able to created a livelihood for himself and his family in South Sudan. He describes himself as a "dibiti parent," a term they jokingly use in his country for first borns who are the first to leave their villages and obtain education. He explains that in such a conflict-ridden country, all their parents lived during war and crisis and have no savings or means to provide for their children. So it becomes the responsibility of the first born to provide food, clothing, pay for education, and even provide parental guidance. He provided these things for 12 family members by working in development and farming. He describes this period as a time when they finally had hope that the conflict would be over. They had hope for a future without suffering. Unfortunately, however, another conflict broke out in 2013, and again in 2015. In this conflict, paranoia from the government that Isaac was feeding rebels with his produce, and a similar distrust from the rebels, lead to his produce being confiscated, leaving him with no income. As a result, Isaac had no choice but to move his entire family to the refugee settlement in Uganda. Of about 1.4 million refugees in Ugandan settlements total, about 848,000 are South Sudanese. Isaac describes the uphill battle the South Sudanese face when arriving in Uganda as a result of not being as exposed to the world and to education as Ugandan people. He says he brought one idea with him to the settlement, “We have to beat all odds. We have to continue beating the odds. The benefits of life that come easily, we have to get to the hard way. We have to turn it around to make it succeed." Isaac did beat those odds, and was the first South Sudanese person in Rhino Camp to obtain a higher professional status when he began working for the Danish Refugee Council. He worked to reduce vulnerabilities facing adolescent refugees, and eventually helped to some of his fellow South Sudanese get jobs. He was working and earning a salary, but still faced difficulties, “While trying to solve other people’s problems, we have our own to solve for ourselves." He explained that as refugees themselves, most of the front line staff had their own families living in the settlement and had also lost their property, livelihood and often family members in the conflict that led them to flee. Additionally, his salary allowed him to take care of his family, but because he had always grown up surrounded by his community, also left him feeling guilty, “I feel bad that I can buy things, like meat, that other people cannot afford. My neighbor cannot afford these things, and this is what many refugee frontline staff face.” The pandemic has made things even more difficult for refugees. Refugees rely almost 100% on humanitarian assistance, and with many donor organizations having to focus their funding on their own countries dealing with COVID-19, they can no longer count on this relief in refugee camps. In April there was a major food rations cut, and in total about 30% of donor funds have been suspended. Isaac explains that to obtain necessarily survival essential, refugees also rely on trade. On walking around the settlements and interacting with one another, which has all been halted due to the lockdown. Furthermore, refugees do not have access to reliable enough internet access to receive updated news around COVID-19 and with many organizational standards lowered due to lack of funding, the staff who used to come in with that information no longer has access to it either. Isaac spoke extensively about the front line staff in these settlements. There is almost no mental health support for frontline staff in Rhino Camp and on top of trying to support the other inhabitants they are also now often isolated from their own families due to lockdowns and travel restrictions. Isaac himself is currently stuck in South Sudan and has no idea when he will be able to return to Uganda to be reunited with his family. He shared that he was present to see his daughter's birth in December but has not seen her since. Aside from all the aforementioned added stressors of this pandemic, Isaac explained that his country and those like it often take cues of what to do in global crisis from Western culture. He says, however, that in a country torn apart by war where most citizens are starving or at risk of severe malnutrition, the approach of shutting down the economy, like we originally did in the United States and Europe, will not work. “People are facing the choice of “die of hunger or die of COVID-19”. Highlighting the need to customize how we approach crises in each country, especially those that are not represented well in global decision making.

Isaac says despite knowing and seeing that the strain related to COVID is continually getting worse, he reports that there is little to no access to testing so it is unclear how much the virus has actually spread. He shared that the hospitals are over capacity, and the shocking fact that South Sudan only has 4 ventilators in the whole country. 4 ventilators in a country of almost 11 million people. Additionally, there is little personal protective equipment available to any of the medical staff. Even without a pandemic, in addition to an already weak medical infrastructure, civil servants, nurses, and midwives do not make enough in a month to buy even 100 kgs of rice. Their payments are also often delayed up to three months at a time, resulting in significant stress beyond the virus. And due to a lack of cohesive communication by leaders, many South Sudanese are not adhering to the guidelines set forth which in turn will put even more pressure on this health care system and it’s workers. In the face of all of this, Isaac and his community are still pushing through. “We still have the hope. And we’re not losing the effort. But I’m quite sure that after this pandemic people will face more serious mental health issues than food and clothes. And it might even kill more people than what COVID-19 is killing.”  Laura Fuchs out capturing smiles Laura Fuchs out capturing smiles In the midst of what feels like each day brings more challenges and unveiling more hard truths, our episode this week is dedicated to recharging through moments of hope, grace, and connection. Sometimes people add to our collective strength in completely unexpected and yet completely necessary ways, and we are thrilled to have found one of those people. Her name is Laura Fuchs, and she is a photographer living in New York City. We found her after her “Mask Smiles” project was featured in an article by BBC, which you can find here. With a degree in psychology from Barnard, and about ten years of photography experience, Laura brings incredible empathy and connection into her art. She shares that she is completely in the moment when taking a photo of someone and how special it is to then give that person their photo. “Photography is 100% therapy for me. It’s my favorite thing.” She encourages everyone in her life to pick up a camera, “It’s an amazing way to document your life, seek comfort in other people or inanimate objects, connect with yourself, and have it reflected back to you.” When the pandemic hit, Laura realized as she walked around New York City that not only did people seem scared, but they weren't even looking at each other anymore. In response to that, she found herself trying to smile at people through her own mask. One day with a passing stranger's returned "smize", she realized that despite masks, smiles could still be acknowledged, and returned, and that felt really special to her. She began trying it out on a few people by asking if she could photograph them smiling behind their masks and “Mask Smiles” was born. “It’s so rewarding to feel as though I’ve kind of re-empowered people with their smile.” Laura shares passionately that this project is not to make light of how hard this time is. Not everyone can smile right now, and she is aware of and respectful of that. Sometimes she meets rejection on the street and acknowledges that her positive energy is not always equal to where people are and explores the idea of how powerful it can be to plant seed for those people in this time. To help people understand, whether they are in a place of deep grief and fear, or whether they are afraid it’s inappropriate to smile at a time like this, that smiling is not an invalidation of how hard this time is. Reminding us “These are smiles of resilience, these are smiles of strength.” And that in the face of all this trauma, it can biologically change your state to even force a smile. Laura shared some of her favorite moments of the project so far ranging from finding a woman in Chelsea who sits on a bench yelling expletives at people not wearing masks, to a day where she experienced the spectrum of first being turned down by an obviously grieving healthcare worker before going on to encounter a larger than life “fabulous” cross town bus driver who enthusiastically participated in the project. She shared a moment of finding a mother and daughter jumping in puddles and emphasized the beauty of seeing people doing regular things. She explored her wonder at the impact this is having on kids by sharing one last story about a family she photographed with young children. Upon approaching and explaining the project to the parents, the mom turned to the kids and said “Guys we were just talking about this, about how you can still see other people’s emotions through masks.” Through all of this, self-care is also really important to Laura. Besides photography, bike rides are her therapy, she says, “It feels so good to move.” She’s also been cooking a lot and watching bad TV. Her confession of bad TV led her to stress how important it is right now to not judge ourselves, “Just do your own thing, don’t judge your progress or lack of productivity. Give yourself a pat on the back for even making it through this period.” In her parting words she leaves us with a simple encouragement to smile. That a simple smile can give you a moment of feeling strong, in control, and centered. On top of that, she urges us to give someone else a smile. Reiterating that we never know what someone is going through, and that while we should be prepared for rejection, the potential for something positive is so much greater than any consequence of a rejection. “It’s good for people to see that they’re allowed to smile right now, it’s good for people to see that they’re allowed to find joy. And more importantly, to me, I think it’s a time to dig deep to find joy. Find that joy.”  Joe Rojas Joe Rojas As our country continues to fight COVID-19 and racial inequities every day, we want to acknowledge how hard this time is for so many people. We have struggled to figure out how to proceed with this project in a way that values and prioritizes both battles. Our mission in starting this podcast was to highlight people who are working to improve our world by caring for others, and in this time of great turmoil, we feel the stories we have collected from those on the front line of COVID-19 will continue to add to a greater sense of healing and prioritizing of self care, and we are excited to continue to share them with you. In this episode, we interview Joe Rojas on his experience of the prison system’s response to COVID-19. One of the reasons we wanted to investigate the prison system during this pandemic is because the conditions in prisons make containing an infectious disease inherently difficult. This pandemic has disproportionately affected people of color, and with people of color making up a disproportionate percentage of the prison population, one of the things we learned from Joe is that prisons are yet another space where vulnerable populations are disproportionately affected by this virus. Joe is a member of law enforcement. He has been a corrections officer in the prison system for 25 years, and he refers to himself and other guards, as the "forgotten law officers." We realize that law enforcement is a very loaded term right now and is at the center of this long and current battle for racial justice. Joe is passionate about advocacy and one of his main missions is to make sure the inherent hazards in the prison system are lowered, and that management upholds their end of the bargain to help make that happen. Joe explains his journey from corrections officer, to eventually getting promoted as a teacher where he focused on helping inmates with GED testing, job fairs, interview skills, resume building, and social skills. In 2005 Joe became a union official, moving up from union president to regional vice president for the southeast region where he now oversees 17 institutions. He acknowledges that working in a prison brings inherent hazards with it, but that his main goal is to prioritize safety. Joe explains that there is approximately one officer for every 128 inmates. That there are a lot of assaults, including staff assaults. He shares that having worked in the prison system for 25 years, he has established bonds with many of the inmates, but that he also has to separate that from his personal life. That many staff members struggle to do so and because of this the divorce rate is high among prison staff, many of them have high blood pressure, and the mandatory retirement age is 57 because otherwise they wouldn’t last. Joe tells us that on top of what can already be a very stressful environment, COVID-19 has introduced a whole new level of stress to both staff and inmates. “I’ve worked in prison for 25 years, I know the hazards. But when you have this invisible enemy that you can’t see, you can’t touch, you can’t do anything. That’s possibly spreading around the institution. I can get it, but I’m more worried about bringing that to my family.”  Robin Nesha Grubbs, 39 year-old case manager who died of COVID-19 Robin Nesha Grubbs, 39 year-old case manager who died of COVID-19 In Joe’s opinion, the prison’s COVID-19 response has been disappointing. The staff sent suggestions of how to combat the virus, including locking down the institutions, closing visitations, and providing masks. However, these guidelines failed to be met. As a result, inmates have died, there are several staff on ventilators, and they lost a 39 year-old case manager named Robin Nesha Grubbs, who died from COVID-19 after being denied a mask while working in an isolation unit. One of Joe's biggest frustrations in this battle for proper protection from the virus, is that Congress allocated $100 million for personal protection equipment (PPE) and overtime to the prison system. Despite that money, the only masks they received were made through inmate labor from incredibly thin material which shrivels up after being washed one time. After speaking out and advocating they eventually received acknowledgement that those masks were not adequate, but still did not receive proper alternatives, leaving the prison staff to wonder where the money went. Joe and his colleagues have made some progress and there are currently inspections beginning thanks in part to the congressional support their advocacy has drummed up. Joe went on to say that, unfortunately, he and his colleagues have been fighting injustices from the agency like this for years, even before COVID-19 began.  Black Lives Matter protest in Brooklyn, NY (photos by Laura Fuchs) Black Lives Matter protest in Brooklyn, NY (photos by Laura Fuchs) This week we have been reminded, again, that there are many vital battles to fight. The United States and the world have witnessed more brutal killings of innocent people, and communities are standing up to fight for justice. In light of what is currently happening in our country, outside of COVID-19, we have decided not to release a new interview this week. The injustices and traumas are so pervasive that we must stop what we are doing and take action. This pandemic is far from over, however, in alignment with our mission of supporting those on the front lines, we have decided that there are many front lines and right now we want to support those standing up against social and racial injustice. To honor the fight for justice and the many people who are experiencing persistent and systemic racial inequities every day, we are offering resources which provide information on how to help either through donation or action. Organizations with Vital Information and Options for Donations: Black Lives Matter, which builds power to bring justice, healing and freedom to Black people across the globe. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), whose mission is to secure political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights in order to eliminate race-based discrimination and ensure the health and well-being of all persons. American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which exists to preserve and protect the liberties and privileges guaranteed to each individual by the Bill of Rights. These liberties include freedom of speech and expression, equal protection under the law, due process of law, and the right to personal privacy. Color of Change., who design campaigns powerful enough to end practices that unfairly hold Black people back, and champion solutions that move us all forward . Campaign Zero is working on reforming law enforcement policies from the ground up through a comprehensive platform of research-based policy solutions. Funds Seeking Donations: Bail Out Spreadsheet with information about bail out funds listed specifically by location, so that you can find your local affiliates. George Floyd GoFund MeSite ‘I run with Maud’ GoFundMe Site Change.org Petition for Justice for Breonna Taylor Resources for In Person Action: "How to Protest Safely During a Pandemic" (Vice) These protests and this cause are vital, and the call to action to show up for your community is valid; and there is still a virus spreading through our states at the same time, so it’s important to answer that call to action as informed as possible.  Dr. Budhrani Dr. Budhrani In this episode, we interview Dr. Budhrani, who has been practicing clinically for over 20 years as an emergency room (ER) physician, is the CEO of Innovation Health, whose goal is to unify the health care system to making the patient experience easier and more affordable, and is a professor at George Washington (GW) School of Medicine. We are grateful that he was able to make the time to speak with us about the impact COVID-19 is having on the medical system as a whole, the mental and physical health of front line health workers and their families, and what resources are available to them. Dr. Budhrani believes it is critical for health care providers to have a seat at the table when discussing what the ‘new’ world will look like and how to get people back to work, back to school, etc. He also explains how coordination of care is key. That healthcare industries need to share data and manage populations in a coordinated fashion to prevent the virus from spreading, and to inform the public health response for future pandemics, or a second wave. He says thinking of COVID-19 as ‘going away’ is a dangerous assumption, but rather thinking about how to manage and prevent it's spread are going to be the keys to our success going forward. Not simply rolling the dice and hoping it will go away. When we sat down with Dr. Budhrani, we were in the midst of the country realizing that although front line staff are ‘heroes’, they are still humans who need support. Right before our interview, news came out that a New York doctor had taken her own life, a doctor in Washington DC announced on social media how difficult it is to bury his emotions, and Governor Cuomo, Governor of New York, committed additional funding to support mental health services for front line staff. We caught him at a time when our country and our listeners needed to hear how to help front line workers and how front line workers can get the support they need. In response to this, Dr. Budhrani describes the stress he feels each time he thinks about entering the ER, with new guidelines and policies being enacted every day. How he leaves home with two layers of clothing knowing the top layer will be exposed and how much he needs to think about things he rarely considered before such as being well-groomed and having adequate personal protection equipment (PPE). Stating that in reality, he is now going in “physically armed” to work. Hearing that, we asked him why he would go back into the ER right now having an already full plate with Innovation Health and teaching. “If you are blessed with the opportunity to have the knowledge to help someone, then I think we feel as though we have a moral obligation to impart that knowledge, especially right now. In our lifetime there has not been a clinical tragedy at this scale that has affected so many lives across the world, and I feel a moral obligation to serve. That’s what drives me to go into the ER.” He explains further that despite feeling hot and claustrophobic in layers of PPE for 10 hours at a time, and how that can make a person “mildly delusional,” in this climate there is something really satisfying about being able to help someone. "I think that is a significant driver of all of us who do this.” “We’re seeing some of the greatest impact on mental health and physical health on these front line folks, and they need to be addressed now so it doesn’t erupt like a volcano later.”  Sherry Bensimon Sherry Bensimon We sat down with Sherry Bensimon, a New York and New Jersey state licensed funeral director, to hear her story of how COVID-19 is impacting her work and home life. We found Sherry after she was interviewed for a New York Times article about how funeral directors are risking their lives to do their jobs. Sherry has given her life to taking care of the dead in all possible ways. From the time she was a teenager, she was a member of the chevra kadisha, a Jewish holy burial group made up of volunteers from the congregation who wash and shroud the deceased to prepare them for burial. She explains that taking care of the dead is very important in her society, “New York is one of the most stringent in terms of taking care of it’s dead. We’re still human beings [upon death]. New York requires special schooling to become advocates for the dead. They can’t speak for themselves, we have to, and that’s why I got into this profession.” A funeral director is responsible for a great mitzvah, a good deed, “I’m the one who is responsible for taking care of the dead. In Judaism, taking care of the dead is one of the highest acts, it’s probably just below saving a life. Had this person not been alive, a small community would not have existed. To do my job is a beautiful, life-affirming thing.” Sherry describes how difficult it has been for her to do her job during this pandemic, “These people died alone and now they are being buried alone. A lot of cemeteries are limiting mourners to 3-8 people at a time. At least I’m there, but the people that should have been there are not. They’re [the deceased] not being given the love and respect they deserve. That is emotionally the hardest for me. How do you tell a family sorry but your cemetery will only allow three people?” “To us, we hold dear so much to our rituals. Here is something that is so important to us, you know, gatherings and funerals are very sacred for a lot of cultures. And that comfort, you just can’t get.”  Alex in scrubs at the hospital Alex in scrubs at the hospital As a physician assistant working in oncology at a multiple myeloma center in New York City, Alex Kaiser gives us a glimpse of what it's like to be a healthcare provider who is not treating COVID-19 patients during this pandemic. She explains how she’s supporting her patients through and how she’s finding ways to support herself. In the first few weeks of the pandemic, Alex and her colleagues had to make quick decisions around which patients absolutely needed to come into the hospital for chemotherapy, despite the risk of COVID-19, and who could wait. This meant conducting a risk/benefit analysis, pausing or drastically shifting some patient's care, and managing patients’ anxiety around these decision. Alex explained how oncology allows providers to establish strong, long lasting relationships with their patients and how because of that she often absorbs her patients’ fears and concerns, making these rearrangements in treatment exhausting. So she quickly came up with a COVID-19 cancer care package (pictured above) to better support her patients. She sent around emails to gather donations (hand sanitizer, thermometers, etc.) and FedEx-ed or hand delivered the packages to her patients. Additionally, after friends shipped her loads of face masks, she started handing them out at grocery stores or gas stations. “Since I wasn’t on the ‘front lines’ of COVID-19,” said Alex, “I thought about what else I could do in my community. You receive when you give.” Despite her hard work and dedication to her patients and her community, Alex explains how many health care workers not on the ‘front lines’ (ie. emergency room, COVID-19 units) are currently feeling a sense of survivors’ guilt, “Because we don’t have N95 (surgical mask) bruises on our faces or we’re not holding patients' hands as they die, it’s easy to feel like I’m not doing enough.” However, Alex discovered that this comparative guilt does not serve her, and decided to take a new approach. Alex explains that self care was not high on her priority list the first few weeks of the pandemic, and her usual coping skills, such as festivals and music shows, were taken away from her due to the shutdowns. She lives alone, her non-medical friends left the city, she couldn’t go outside to run, and she felt a sense of anxiety. She asked herself the question: what serves me and what doesn’t serve me? In answering that question she decided to take a hard look at her social media life. It had become really difficult to look at people spending their "social-distancing" time at the beach or at a lake, so she un-followed some of those friends. Instead, she reached out to social media to find support. As a Phish fan, she posted in a Facebook group called ‘Phish Chicks’ asking if anyone would be willing to send her mail since she was feeling lonely. She immediately began receiving packages or letters every day, and plans to reciprocate the gesture when things settle down. She went on to share that she began really paying attention to the little things as a way to find relief. She tried adding color to her apartment, she began collaging, she also figured out that getting to the grocery story and preparing food was something that was causing anxiety. With her parents 45 minutes away in Long Island, she was able to out source this task to them. Her parents would ask for a menu each week, cook a fridge worth of food, and drive in to drop it off and visit with masks on from six feet away. “I’m hopeful that this could be a reboot for mankind, and good things could come out of it, not just bad things. That we could somehow all unite together.”  Rouben in an empty airport before his last shift as a flight attendant before getting sick Rouben in an empty airport before his last shift as a flight attendant before getting sick Rouben Madikians is a flight attendant, yoga teacher, photographer, and COVID-19 survivor. His story inspires us to look for connection even in the isolation, and that being vulnerable takes strength and courage. After a few days of feeling foggy and disoriented, Rouben eventually developed a fever and tested positive for COVID-19 while on a layover. Due to that he was forced to self-isolate in a hotel for two weeks. Despite being scared, alone, and feeling terrible, what Rouben shares from this experience is how held he felt by the hotel, his family, and his co-workers. Highlighting his commitment to looking for connection even in separation. Rouben reflects on those two weeks in quarantine, as well as his experience working as a flight attendant during the pandemic, “I miss touching someone on the shoulder, hugs from my friends, shaking my passengers’ hands, or taking a child to the flight deck.” He descirbes a story of infant twins who were hospitalized while ill. Once their nurse put them in the same incubator, one child put their hand on the other, and their vital signs changed almost immediately. This story, he says, shows that we are "social beings." That physical touch physiologically makes him feel better. Rouben’s experience has been that admitting this is vulnerable, and that sometimes people equate vulnerability with weakness. To that he says, “So be it, fuck it.” The feeling of loneliness is so real for so many right now, and even if we’re with other people, we may still feel alone. Rouben explains, “Either we don't have bandwidth [to engage deeply], or there are just so many layers in between us and that person, forcing us to shut down. If I’m shutting myself down to the negative feelings, I’m shutting myself down to the positive...it’s the same neural pathways.” Rouben expressed extreme gratitude for the generosity of family, friends, flight attendants, his company, and the hotel staff. However, his biggest fear is that he could have spread the virus to others before it was detected. Frontline employees don't get tested until they show symptoms. Rouben didn’t have symptoms until about six days into his illness, and even after he had a fever, he had to obtain a prescription in order to be tested. “We need to be tested, no questions asked,” said Rouben, “I hope the rules change around that.” "Maybe I needed to get covid to go deeper into this. So, in a way, I'm grateful."  Felicia Temple. Photo courtesy of https://www.prlog.org/12796611-felicia-temple-of-the-voice-to-perform-at-nurses-pub-gala-future-nurses-to-rise-to-the-occassion.html Felicia Temple. Photo courtesy of https://www.prlog.org/12796611-felicia-temple-of-the-voice-to-perform-at-nurses-pub-gala-future-nurses-to-rise-to-the-occassion.html So much has happened since we first launched this podcast: we changed our name to “Finding the Helpers: Presented by Playing to Live”, received loads of support and excellent feedback for the show, and have lined up several amazing guests for the next few episodes. We are thrilled to bring you episode number two of the podcast, with Felicia Temple: contender on The Voice in 2017 and ICU nurse. Felicia has been receiving media attention in the past few weeks since an interview during Global Citizen's "One World: Together At Home” concert, which is how we found her. Having finally made the decision to take a break from nursing and pursue her musical dreams in early 2020, she was on an international music tour in Brussels when she found out that the US planned to close its borders due to covid-19. Within a week, she was “rolling up her sleeves” and getting back to work at her former nursing job at Holy Name Medical Center, but this time in the newly set up covid-19 ICU. She says she returned to what felt like a different hospital, even though she had only been gone for a few months. She experienced culture and shell shock. They were building new ICUs, everyone was wearing masks, and there were tubes going in and out of rooms to set up negative pressure for isolation units. Despite all of this, Felicia felt called to be back on the front lines with her former coworkers, in a job she has always loved. Her biggest personal challenge is not being able to see her family. In this episode, Felicia describes going past her family’s home every day on her way to work, knowing that she cannot stop to see them. Her mother is immunocompromised, so working with COVID patients means she had to stay away. She has also lost two aunts in the past week from covid-19. Death is all around her, and she’s now afraid to look at social media for fear of finding out who was the next in her community to be taken by the virus. Not only is it difficult being away from her family, but being a healthcare worker is a huge emotional burden during this time. Felicia describes what it feels like to hold someone's hand as they die, because they cannot be with their family. She has a new appreciation for the rituals that our society has around death, and is appreciative for the iPads they have at the hospital, allowing patients to say goodbye, virtually, to their families. “There’s so much to process. It’s like going to war. I’m not going to be able to process this until the world is somewhat back to normal and I can really sit down and unpack it.” |

AboutIn Season 1 of Finding the Helpers, we are bringing personal stories of front line staff and families impacted by COVID-19. Our diverse guests will be invited to share their story of being on the front line, and in combination to their story, two expressive art therapists will provide art and creative activities that will support the challenges the individual and their family is facing. These could include ideas for short relaxation techniques to be done on the front line, creative ways to explain in kid friendly terms what is happening, ways to stay connected to family and children during long periods of isolation, etc. Throughout the podcast, conversation will include mental health insight related to the pandemic, anxiety and stress, grief and loss, resiliency, coping skills, and understanding the pandemic. Presented by the nonprofit Playing to Live's, whose history began in 2014 as a grassroots program focused on bringing play and creativity in the midst of the Ebola deadly viruses. Following our work in Ebola, we have continued our work as advocates and creators for play and expression across the globe in refugee settings, post war countries, and in the United States of America.

AuthorLindsay Bingaman is the Regional Program Manager for Playing to Live, based in Nairobi, Kenya. Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed