|

We are ECSTATIC to announce that UNICEF has provided Playing to Live-Liberia with a 6-month grant. This grant is made possible by our partnership with RESH and our close working relationship with the Liberian Ministry of Gender and the Survivor's Network.

As part of the new UNICEF grant, Playing to Live's team will expand to 40 new program associates, all women who survived Ebola, like Decontee and Helen! The program will last 6 months, reaching 800 children who are affected by Ebola in their communities through play and art recreational activities. The program will also offer support to the parents and guardians of these children through 40 social workers who will provide weekly visits. Playing to Live will train our program associates and the social workers in our expressive therapy training curriculum. The training covers essential tools in working with children who have experienced trauma. It guides the trainees to understand how to utilize their cultural arts to support relationship building, safety building, communication, and emotional expression. The expressive therapies (art therapy, play therapy, yoga therapy, music, and child life) are evidence based practices that are essential tools to trauma recovery. By using expression and art, we are supporting the cultures we work in to build sustainable and relevant programs, and we are teaching child friendly techniques. We can't stop here. With large programs come large responsibilities, and we need your support more than ever. Please consider donating to our cause. Our initial donors provided us the ability to build this program, and we need more than ever the support to make this a SUCCESS!! If you are an expressive therapist, PLEASE visit our donation page on our website. We have an opportunity for you to make a hand print in our global work. Please follow the instructions and donate now and often! The activities you create will be the core of our program. To everyone: This is a HUGE step in our grassroots initiative, and we absolutely need YOUR voice to carry us! Please share our story.

0 Comments

We at Playing to Live! have been SOO excited to present to you something that has been in the works for a month. It means that we will grow far beyond what we have been capable of thus far in Liberia, and we will be able to make a LARGE impact on the mental health of children recovering from the effects of Ebola.

We will be announcing this Monday, and in preparation we are asking everyone to prepare to help us share this story and growth. With your voice, donations, and help, we have the true ability to make history!

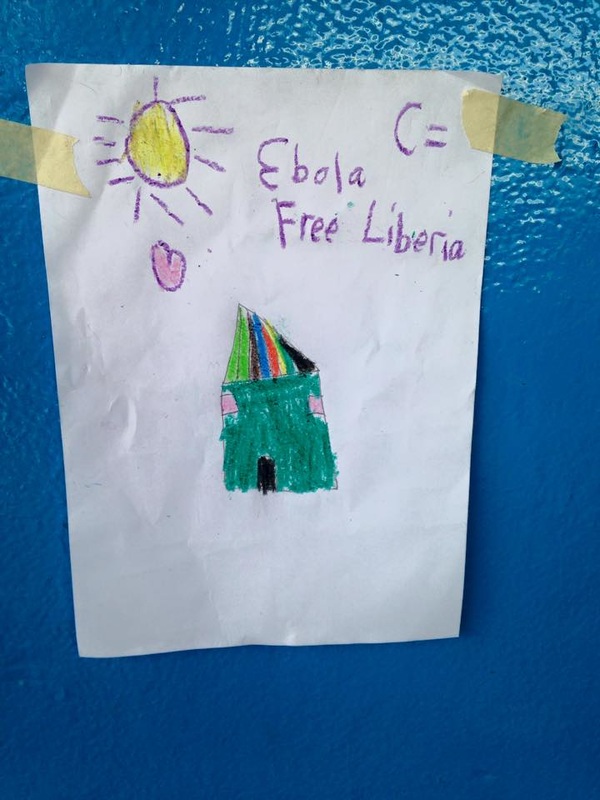

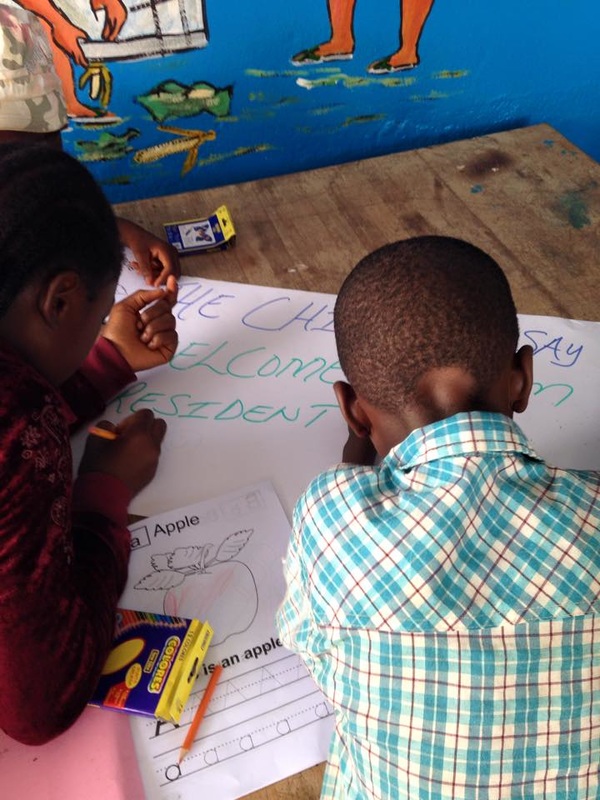

Her mother had many children mostly boys younger. When at an age she thought she would give birth no more, Decontee’s mother gave life to her last baby, a girl. In her pa’s mother tongue, Mandingo, her name meant ‘everything have time.’ Her ma said that Decontee was put on this earth as a gift from the Lord, a precious gift. She would eventually fall in love with an incredible man, a pastor of her church. They were deeply in love and had a son together. “He was not of this earth,” she recalled later, her lower lip trembling as she remembered his face and the way his gaze searched her. They lived together in Mount Barclay near her fiancé’s family, and not far from her own. The first person in their family to get sick was her fiancé’s aunt. On July 29th, Decontee entered the house with other family members to care for the aunt. Rumors of Ebola up in Lofa spreading into the capital of Monrovia were frequent on the radio, but no one thought at the time that this was the case. Peter’s aunt was nauseous, vomiting, and weak. Decontee and the others thought it was just a normal sickness, maybe malaria or a case of typhoid. The poor woman moaned in pain and she had a fever that seemed to worsen each hour. She sweated and came in and out of consciousness. That afternoon, Decontee cooked rice for a simple meal and spoon fed it to her aunt-in-law. Within minutes, the woman lost her stomach all over the floor. Some of the vomit splattered on Decontee’s skin. It was speckled with blood. Disgusted she wiped it off and with the other women in the room helped clean up the mess. “I bathed her, my aunt-in-law,” Decontee explained. “I couldn’t leave her.” As the next day awoke, the aunt -in-law grew worse, and eventually died. Decontee’s fiancé suggested that they call the burial squad to pick up the body, but his family insisted in a traditional funeral. The body was washed, dressed and prepared for burial by close family members. A few days later, more people in the family suddenly grew very sick and also died, including a young child. That week, Decontee returned to be with her mother and son, James. Her fiancé traveled to oversee the preparation of the additional funerals. Decontee planned to join him the day of the burials. She would not make it. On August 5th, Decontee awoke in her family home with a headache that felt as if someone were using a sharp object to split open her skull. She felt cold. There was a chill deep in her bones. When Decontee’s ma saw her beloved daughter sick, she became fearful. Something was not right. Worse, her son was showing symptoms. Her family took them to a pharmacy and then a clinic for testing. They were told it was malaria and given treatment. Her son responded, but Decontee’s condition continued to worsen. Her fiancé was also showing symptoms similar to Decontee. At the clinic, a health worker advised Decontee to go to the Ebola Treatment Unit (ETU) to be tested for Ebola. Decontee’s uncle who was with her at the time said it was not necessary, but Decontee’s father insisted she go to the ETU. She chose to follow her father’s advice, and her brother and aunt brought her to the ELWA 2 ETU. There was a line for admittance so she was laid on the ground to rest and wait her turn for screening. Her brother fed her coconut water which she vomited up black. Everyone around her and her brother moved away from her, and she grew scared. A nurse came out to assess her in a haz mat suit (PPE), and said it seemed she had Ebola. Decontee didn’t want to believe the nurse. “Don’t embarrass me. I not Ebola patient,” she said “Don’t embarrass me. I not Ebola patient,” she argued. It was not until she overheard a mother comforting her daughter close by that going into the ETU could save her life. The woman said she heard of people who had survived the Ebola coming out recovered. This gave Decontee hope for the first time that entering the ETU could mean surviving, not dying. She called her fiancé to tell him she was going in. No cellphones were allowed inside, so it was her last chance to speak with him. He was very sick, and she convinced him to come immediately to be with her in ELWA 2. When she was admitted, she was sprayed down, her clothing changed, and she was left alone in the ETU ward. She received wonderful support from the medical team whose faces she could never see through their haz mat suits. The doctors offered words of encouragement and prayed with her. She tried to keep a positive mind as she say that those who gave up to their misery often died quickly. She had moments of horrible pain and the sense of loneliness and fear of death. She was very ill for several days before the treatment started to have an effect. When she was finally awake and her fever lessened, she realized her fiancé was still not with her. She begged for the staff to track him down. The family said that he was there and that he was alive. Decontee was still very sick and could not move about. She had hours where she came in and out of consciousness. During one of her harder days, she thought she heard her fiancé crying and screaming over the hundreds of beds in the ETU. She could not see him. The staff could not locate him and her family insisted that he was there at the center and was on IV drip. Decontee was told later by Dr. Brown, one of the ETU heads, that her fiancé had perished to Ebola days before. They never saw one another while they were sick. She was not able to bury him and he has no marked grave for her to tend. She was beside herself with grief. Friends who had been with her in the ETU recovering alongside her supported her through this loss, they themselves all going through similar personal tragedies, racked with survivor’s guilt. On September 1, Decontee was released with others as an Ebola survivor. She came out skinny and weak, wearing a plain white shirt, a donated shirt and flip-flops used as bath slippers. That day she was the first in the country to donate one pint of her blood to help cure a dying woman with her same blood type. The woman survived. Decontee felt a sense of meaning. She knew her new path would be devoted to helping those suffering as a result of Ebola. Her uncle came to pick her up from the ETU. She carried in hand the official certificate validating she did not have Ebola. And while most of her family were very supportive, there were those of her friends and family who could not be so open-minded. Decontee and her family faced stigma upon her return. Her son was forbidden from playing with neighbor children because his mother has ‘Ebola in her blood.’ Their house had little left as most belongings had been sanitized or destroyed after she was admitted. She had little money, and most of the men who were the breadwinners in her family were gone. Decontee went to the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare to apply for a government job offered specially to survivors. She was assigned to work in the Interim Care Center with children who were not Ebola confirmed but Ebola suspect, and had to undergo a mandated 21 day quarantine in the ICC. Decontee received training and support by ChildFund and the Ministry. She soon was placed as head of the ICC caregivers, supporting a team of 9 caregivers (all survivors) and up to 20 children in the center. When Playing to Live! was first introduced into the ICC for piloting, Decontee was one of the first caregivers to jump on board. She helped organize the other caregivers to receive orientation on the art and play activities, practice them first, and then replicate them with the children an hour later. Decontee taught the younger children how to hold their crayon and pencil, how to draw shapes and objects they wanted to, and also provided feedback on the activities to Playing to Live Program Manager, Jessi, as to how to better improve them. Decontee openly shares her story of survival and supporting others affected by Ebola, and is an advocate against stigmatization of Ebola survivors in Liberia. She has given public speeches and has had her story featured on ABE and NPR. UNICEF also did a social media piece on Decontee that received thousands of ‘Likes.’ “I have to give back,” she says, “We have to move forward together. Ebola will end. We will help kick it out of Liberia.” |

Welcome to Our Blog!

We will be providing you with stories of the communities we support. The children and their caregivers featured in this blog have provided consent to share their art, pictures and stories. Archives

April 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed